Project Four: Clustering the Future - Leveraging Collegiate and Athletic Data to Find NFL Comparisons for College Players

I. Introduction

As I am writing this blog post (which, very sadly, marks the last project for ITCS 3162—really enjoyed doing this), the NFL Draft is just a few days away. Across the NFL, thousands of scouts, analysts, general managers, and certainly fans are making predictions, countless mock drafts, and trying to see which incoming NFL player is going to take the league by storm.

One of the most common discussions amidst this frenzy is the notion of player comparisons, where an incoming college player is evaluated in the backdrop of an already-established NFL receiver based upon a variety of characteristics, typically physical. However, while the “eye test” for this sort of comparison might be really helpful for general ideas and comparisons, it is not nearly as robust and quantifiable as it could be. Additionally, while these comparisons tend to gravitate certain archetypes of players towards a single NFL-prototype, that tends to embody the entire subgenre of wide receiver instead of looking at a more holistic viewpoint that includes other viewpoints. For example, incoming Ohio State prospect Emeka Egbuka has gotten countless comparisons to current Seahawks wide receiver Jaxon Smith-Njigba, and rightfully so, as the two possess incredibly similar route tendencies and also attributes. However, Smith-Njigba himself is part of a larger group of wide receivers who prioritize their game on flawless route running fundamentals, tempo, and QB-connection as compared to the “muscle-first” approach of someone like D.K. Metcalf or Mike Evans. More players outside Smith-Njigba certainly exist for these types of comparisons, and it feels like finding them is a vital step in creating a more comprehensive draft procedure.

With all of this mind, this project attempts to answer What are the major wide receiver archetypes in the NFL? What are their characteristics? and How do the incoming crop of wide receiver prospects compare to those already in the league?. As the previous projects had their main topics of regression and classification, this project tackles yet another major pillar of the machine learning space: clustering. This problem is especially helpful for a clustering project because there are no labels or ground truths on what these clusters even are and what players belong to what, making it an inherently unsupervised learning problem. Though we won’t have an explicit metric to analyze like previous projects, our analysis can be a lot more humane and qualitative, using our judgement and knowledge of these receivers to judge our model’s performance.

I.II: Where did this data even come from?

Like last project, this kind of NFL analysis does not really have a super readily available dataset all cleaned and ready to leverage (or even created at all). Thus, it was up to me again to create it and standardize it into a usable format to ensure that this project could even be made. This project demanded data sources not just from the NFL but also college, thus I enlisted the help of 4 discrete data sources to help me out:

-

nfl_data_py: Leveraged this in Project 3, but this project is awesome as it includes a bunch of NFL data, but most importantly for my project, a slew of roster data about every player in the NFL, such as their draft position, age, and headshot (which is vital for my tables!) -

cfbd-python: The college football API that provided all of the statistics and advanced analytics for the college side of things. This package is very well-documented and though it requires an API key, the free tier is very generous at 1,500 requests per month and I got an extra 1,500 requests as a student. I only ended up needing around 30-40 requests amid all of my mess ups and such, but still nice to have! - nflcombineresults.com and Reddit: Just like NFL salary cap data, getting combine data is surprisingly really difficult and annoying to retrieve.

nfl_data_pydoes have a method for this, but the data is kinda outdated and not very well filled-in, so I was forced to end up finding a website I can quickly scrape. I only issued 3-4 requests and then saved the data to a CSV to prevent spam, and the data here is much higher-quality than thenfl_data_pyequivalent. For 2025 data, that wasn’t yet available yet on nflcombineresults, so I found an awesome spreadsheet that someone had made and I could download off Google Sheets. - RAS: This statsitic is kind of the heart of my entire project. RAS stands for “Relative Athletic Score” and it essentially is a single metric to quantify a player’s entire performance at the combine, which means one metric to measure how fast, strong, agile, and overall physically fit a player is. The website is super easy to use and thank the stars for the owners as they introduced a simple button to save a query on the website to a CSV file, absolute legends.

There is a brief discussion below about how the data from these sources is specifically gathered and combined, but that is the overview!

If you’d prefer to download this notebook, just press here.

I.III: What is clustering?

Before we get too immersed in the project, it’s worth taking a step back to define clustering and one if it’s main types: k-means. As mentioned earlier, clustering in an unsupervised machine learning model that tries to deduce patterns from our data by comparing how similar each point is to other data points. While classification does a similar task, clustering does not have labels and our algorithm must essentially determine or create these labels from scratch. To find this similarity, clustering algorithms use distance metrics like Eucledian or Manhattan to and then can make decisions based upon how close a point is to another.

K-Means clustering leverages a pre-defined number of clusters (or classes) as a hyperparameter and then classifies each data point by computing the distance between that point and the distance to each one of our cluster’s centers (called a centroid). To classify a point, we simply take find the closest distance of our point to a cluster’s centroid and voilà, our data point now belongs to that cluster! We then recalculate the group’s center with this new data point, and then repeat this process until our points tend to converge to a single center centroid or a max number of epochs is reached.

II. Pre-Processing and Visualizing the Data

I won’t go into the specifics of the data gathering because it was kind of a pain in the ass, but I will quickly summarize how it went below:

1. Loading the RAS Data

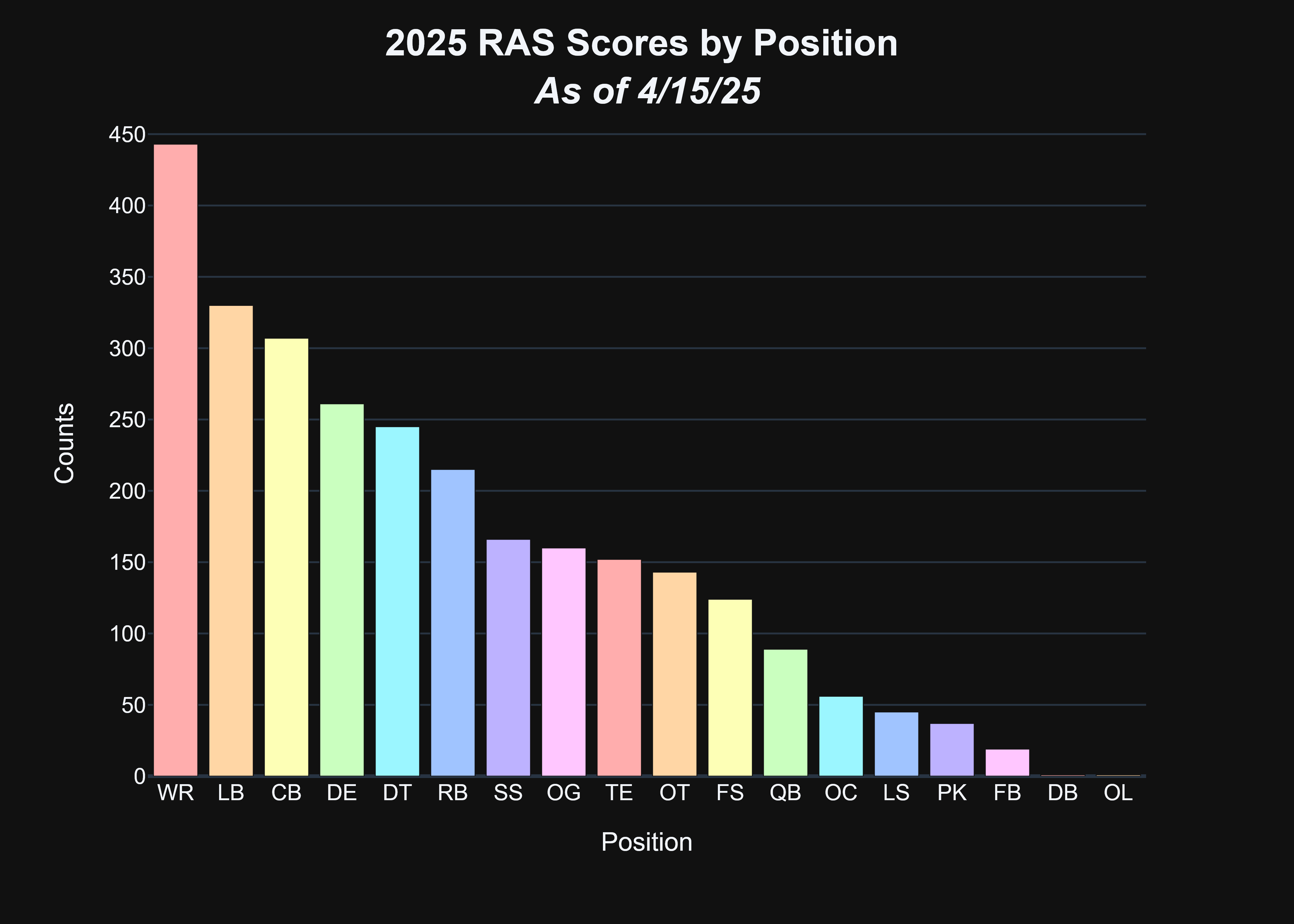

The RAS data was already in some nice spreadsheets, so I simply just loaded it in and then parsed it out to only have wide receivers. You might be asking: Wide receivers again, why? Well, it was honestly because that gave me the highest pool of data to work with for the upcoming draft picks. This draft has a great deal of receivers to be drafted, and though that is likely true most years, this fact combined with the number of analytics that exist for receivers from the cfbd_api made it an easy choice.

RAS_parsed: pd.DataFrame = all_RAS.loc[(all_RAS['Year'] >= 2021) & (all_RAS['Pos'] == 'WR')].dropna(axis = 0, subset = ['RAS', 'Name'])

RAS_2025_receivers: pd.DataFrame = RAS_2025.loc[RAS_2025['Pos'] == 'WR'].dropna(axis = 0, subset = ['RAS', 'Name'])

2. Getting the College Football Data

Given I had to call an API for this, I decided to just create a function that took in a specific metric I wanted and the years I wanted it for. I only used it twice, but it will make getting metrics super easy if I so wish.

def get_cfbd_data(config: cfbd.Configuration, years: list[int], api_instance: str, api_call: str, filepath: str, display_usage: bool = False, load: bool = True, **kwargs) -> pd.DataFrame:

"""call the CFBD api multiple times, conglomerate the data, save it to a CSV and dataframe, and then return the dataframe

Args:

config (cfbd.Configuration): configuration object to authenticate the CFBD api

years (list[int]): years to collect the data for

api_instance (str): the specific unauthenticated API type from CFBD where the specific API call is housed

api_call (str): specific API call that you'd like to make for each year

filepath (str): filepath to either write the file to (if load = True) or read from (if false)

display_usage (bool, optional): display the number of API calls remaining for a given API key. Defaults to False.

load (bool, optional): whether to load a dataset from an existing filepath. Defaults to True.

Returns:

pd.DataFrame: dataframe of requested statistics, either loaded or collected from the API

"""

data: list = []

if not load:

with cfbd.ApiClient(config) as api:

# Get the desired class from the cfbd module

api_class: Type[Any] = getattr(cfbd, api_instance)

authenticated_api_instance: Any = api_class(api)

for year in years:

# Get the method from the class

retrieved_api_call: Callable[...,Any] = getattr(authenticated_api_instance, api_call)

# Make the API call (finally...)

response: ApiResponse = retrieved_api_call(year = year, **kwargs)

# Add this data to our list

data.extend([dict(player) for player in response.data])

if display_usage:

print(f"The amount of API calls left is: {response.headers['X-Calllimit-Remaining']}")

df: pd.DataFrame = pd.DataFrame(data)

# To avoid having to run these API calls every time, we save the file

df.to_csv(filepath)

else:

# In case we already have the file saved, just read it

df: pd.DataFrame = pd.read_csv(filepath)

return df

I then had to parse some of the data down to de-duplicate it, removed team-level statistics and only have player-level values, and also pivot some of the values as some of them were in a weird format where all of the metics were in one column instead of being in their own column.

3. Combine Data

This data was the most annoying to get because as I said, it didn’t really exist in a nice format with enough robustness. For the nflcombinedata.com, I leveraged BeautifulSoup again and that worked perfectly. I tried to keep this scraping to a minimum as the website throws a 404 error technically when you request it, but the HTML data is still received, which is my guess of them saying “please don’t spam us.”

For 2025 data, I used the spreadsheet above but did have to do some pre-processing as the rest of the combine data had the heights of each player in inches while this spreadsheet had it in FIIE values (Feet, .Inches-Inches, Eights-of-an-Inch). I created a small helper function that did this and then overrode the values in the height column.

def convert_fiie_to_in(fiie: int) -> float:

"""convert a fiie height to inches

Args:

fiie (int): height in fiie

Returns:

float: height in inches, rounded to closest hundredth of an inch

"""

fiie_str: str = str(fiie)

feet: str = fiie_str[0]

inches: str = fiie_str[1:3]

eighth_of_inch: str = fiie_str[3]

height: float = (int(feet) * 12) + int(inches) + (int(eighth_of_inch) * (1/8))

return round(height, 2)

# Convert FIIE heights to inches to match the rest of the data

combine_data_2025['height'] = combine_data_2025['height'].apply(func = convert_fiie_to_in)

4. Putting it all Together

With all of this data now loaded but in different dataframes, I had to consolidate the metrics I wanted into one place. I focused on both physical and a player’s prior season statistics for a reason I’ll discuss in the next section, but both are key components of my clustering.

def get_val(player_name: str, col_name: str, dataframe: pd.DataFrame, year: int, year_name_col: str ='year', player_name_col: str = 'name', verbose: bool = False) -> float:

"""Filter a dataframe to find the specific statistic for a player in a particular year

Args:

player_name (str): name of the player

col_name (str): name of the column that holds the desired statistic

dataframe (pd.DataFrame): dataframe to filter with

year (int): year where statistic was captured

year_name_col (str, optional): name of the year column for the dataframe. Defaults to 'year'.

player_name_col (str, optional): name of the player_name column for the dataframe. Defaults to 'name'.

verbose (bool, optional): display instances where no data was found for a particular player. Defaults to False.

Returns:

float: _description_

"""

player_stats = dataframe.loc[(dataframe[player_name_col] == player_name) & (dataframe[year_name_col] == year)]

# the pandemic messed up some of the players due to COVID opt-outs or some players had injuries, if that is the case, we can try looking at a year before the provided date

if player_stats.empty:

player_stats = dataframe.loc[(dataframe[player_name_col] == player_name) & (dataframe[year_name_col] == year - 1)]

# Filter by additional parameters if desired

# for col, val in args:

# player_stats = player_stats.loc[player_stats[col] == val]

# Convert to array and grab the value if possible

if len(player_stats) == 1:

return player_stats[col_name].to_numpy()[0]

else:

if verbose:

print(f'No data for {player_name} for {col_name} in year {year}')

return None

rows = []

# In order to make the most high-quality predictions possible, I am only going to focus on players that I have RAS scores as that is my smallest dataset for and then get college data from their previous data from along with their more advanced metrics

df: pd.DataFrame

for player, year, RAS in RAS_parsed[['Name', 'Year', 'RAS']].to_numpy():

# print(player, year)

row = {

'player_name': player,

'headshot_url': get_val(player, 'headshot_url', nfl_data, year, 'season', 'player_name'),

'receptions': get_val(player, 'REC', receiving_stats, year - 1, 'season', 'player'),

'yards': get_val(player, 'YDS', receiving_stats, year - 1, 'season', 'player'),

'touchdowns': get_val(player, 'TD', receiving_stats, year - 1, 'season', 'player'),

'yards_per_reception': get_val(player, 'YPR', receiving_stats, year - 1, 'season', 'player'),

'average_passing_downs_ppa': get_val(player, 'average_passing_downs_ppa', player_predicted_points_combined, year - 1, 'season', 'name'),

'average_standard_downs_ppa': get_val(player, 'average_standard_downs_ppa', player_predicted_points_combined, year - 1, 'season', 'name'),

'average_third_down_ppa': get_val(player, 'average_third_down_ppa', player_predicted_points_combined, year - 1, 'season', 'name'),

'height': get_val(player, 'height', combine_data, year, 'year', 'name'),

'weight': get_val(player, 'weight', combine_data, year, 'year', 'name'),

'forty': get_val(player, 'forty', combine_data, year, 'year', 'name'),

'RAS': RAS,

}

rows.append(row)

df: pd.DataFrame = pd.DataFrame(rows)

I had a little bit of pre-processing after this due to some null values, and to ensure that I was going to be able to make actual clusters, I eliminated values that were less than 70% full.

# Drop columns where more than 70% of values are null

df = df[df.isnull().mean(axis = 1) < .3]

# Very few values are missing, so we can just impute them with the median for the column

df['average_passing_downs_ppa'].fillna(df['average_passing_downs_ppa'].median(), inplace=True)

df['average_standard_downs_ppa'].fillna(df['average_standard_downs_ppa'].median(), inplace=True)

df['average_third_down_ppa'].fillna(df['average_third_down_ppa'].median(), inplace=True)

This same process was essentially repeated for the college data as well.

III. Data Understanding / Visualization

Some of this was already done in the previous section, but I mentioned that physical data cannot be the sole factor in our clustering. Observe the following:

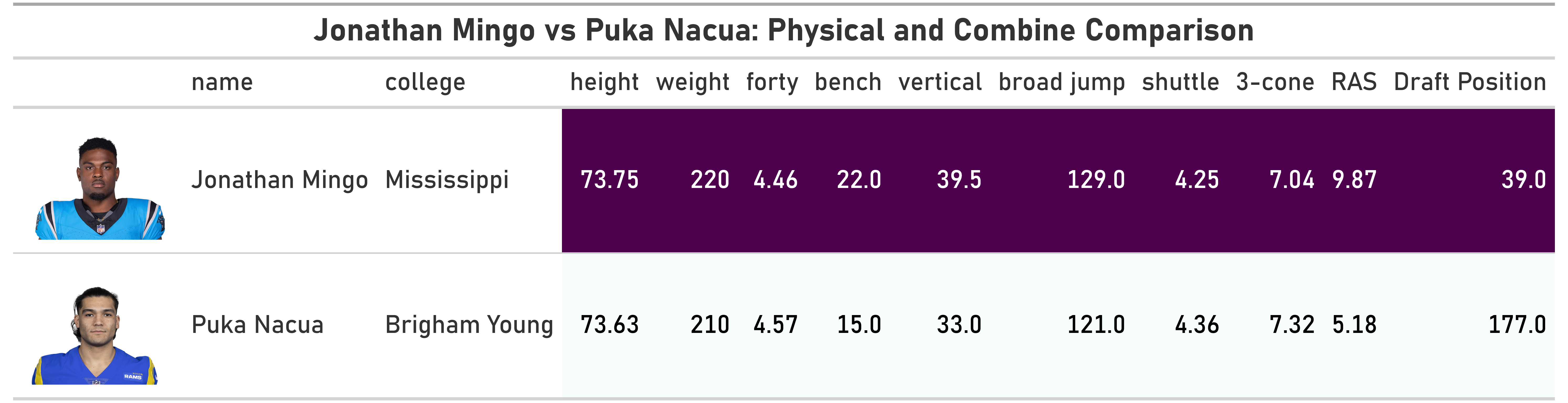

Both Jonathan Mingo and Puka Nacua were drafted in the 2023 NFL Draft. Mingo was one of the draft’s most touted prospects, being drafted in the second round, while Nacua was unknown to most NFL fans, drafted in the fifth round. 2 years later, the lives of these two young men are entirely different: Mingo is already on his second NFL team after being traded for a fourth-round pick and has never posted more than 70 receiving yards in an NFL game and has yet to catch a touchdown. Nacua was a second-team All-Pro selection and a Pro Bowler in his rookie year, and likely would have repeated such a feat in the most recent season if he didn’t miss 6 games (he still had a very good season, nevertheless). The discrepancies in these two players may be obvious in hindsight, but the physical comparison above is just as diverging as these two players’ career paths: Mingo absolutely wins over Nacua and that is indisputable. How Mingo outweights Nacua by 10 pounds yet is still noticeably faster than him and considerably stronger illustrates the two outlooks on the players prior to the draft.

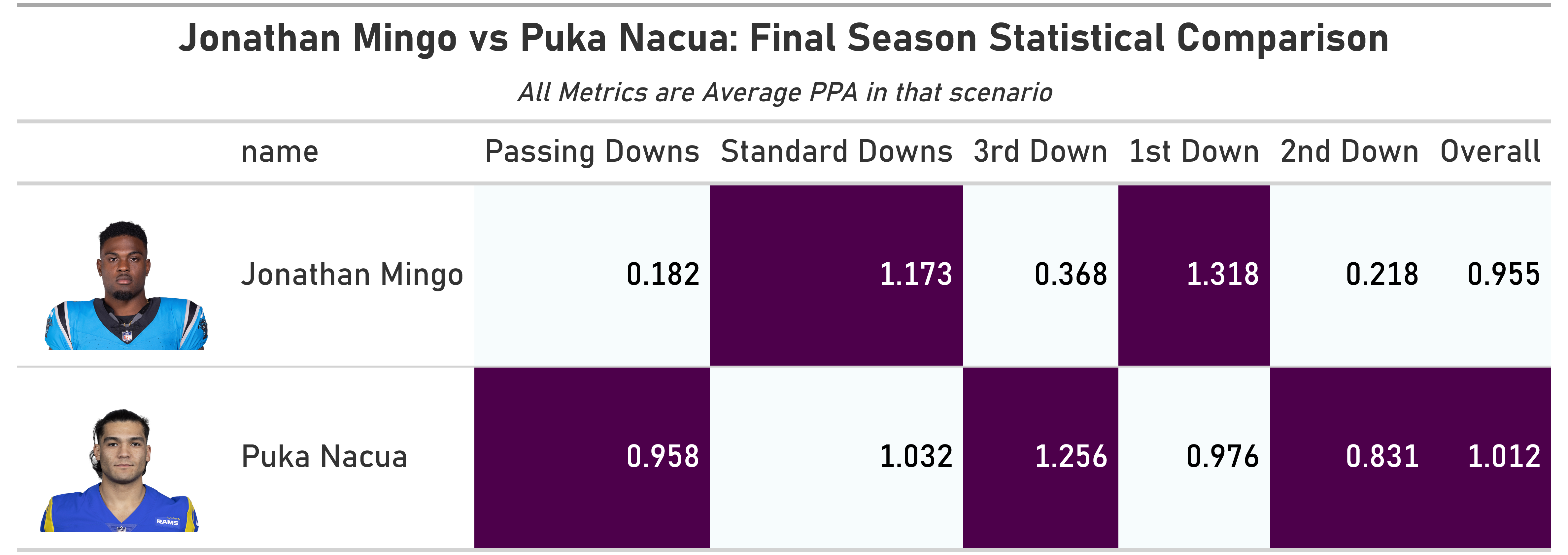

However, as I realized, physical characteristics don’t tell the full story and when we look at how each player performed, we get to get a much more holistic picture of the players’ performance.

We begin to see that Nacua was a far better receiver, particularly on the ever-important 3rd-down that teams need, and while Mingo might have more visible “big-play” potential, the fundamentals of Nacua game is what have made him such a dominant force at the next level. There of course caveats to this comparison (Mingo’s competition at Ole Miss was far better than Nacua’s at BYU), but including statistics to me is a valuable feature to have in our analysis.

IV. Clustering and Modeling our Data

With all of our data retrieved, pre-processed, and scrutinized, the modeling step has finally arrived! To kick off things, we first need to standardize our data because we working with distances and having vastly different scales for our data can create a very weird scenario where our data may be very close together in one dimension but thousands of units apart in another.

# First, we likely need to scale our data

# Keep player_name and headshot_url separate, scale all numeric features

scaler: StandardScaler = StandardScaler()

features_scaled: np.ndarray[float, float] = scaler.fit_transform(df.iloc[:, 2:])

# Create a DataFrame with the scaled features

df_scaled = pd.DataFrame(features_scaled, columns=df.columns[2:])

With that accomplished, we can start by clustering our data for NFL players and figuring out the overall clusters present across the league. I decided to leverage a K-Means algorithim here because will be making a lot of new predictions, which K-Means tends to excel at as compared to hierarchial clustering, and because I wanted to control the number of clusters that were created. While having the variable number with hierarchial is great, it doesn’t really help me if there are three random receivers grouped together and I have no idea why. With a pre-defined number, I can get a general sense of the receivers within that cluster and analyze the commonalities between them without being super time-intensive.

kmeans = KMeans(n_clusters = 4).fit(df_scaled.iloc[:, 2:])

df['cluster'] = kmeans.labels_

While we can certainly just walk through the clusters for all the players and analyze them that way, an amazing way to really visualize our clusters, even with a large number of features, is Principal Component Analysis (PCA). This helps transform our high-dimensional data into a lower-dimensional data while preserving as much of the essential components of the features as possible. As always, plotly makes making these types of visualizations super easy and my theme allows for interactive plotly diagrams, so I made some 3-D scatterplots to explore our clusters!

pca_curr: np.ndarray = pca.transform(df_scaled.iloc[:, 2:])

df['pca1'] = pca_curr[:, 0]

df['pca2'] = pca_curr[:, 1]

df['pca3'] = pca_curr[:, 2]

clusters: px.scatter_3d = px.scatter_3d(

df,

x='pca1',

y='pca2',

z = 'pca3',

color='cluster',

hover_name = 'player_name',

)

This is so cool, and I think really allows us to see the clusters “come to life.” We can also see some of the outliers that I might want to keep in mind when reaching our final conclusions (cough, Jaxon Smith-Njigba and Xaviet Worthy and Tank Dell).

I then repeated the entire process thus far for the new draft prospects, and created a similar PCA visualization for them based upon the clusters we defined for NFL receivers.

This was brief, but this really concludes the bulk of clustering work. Now it’s time to delve into the clusters and see what they tell us about the current landscape of receivers and the next generation!

V. Analysis

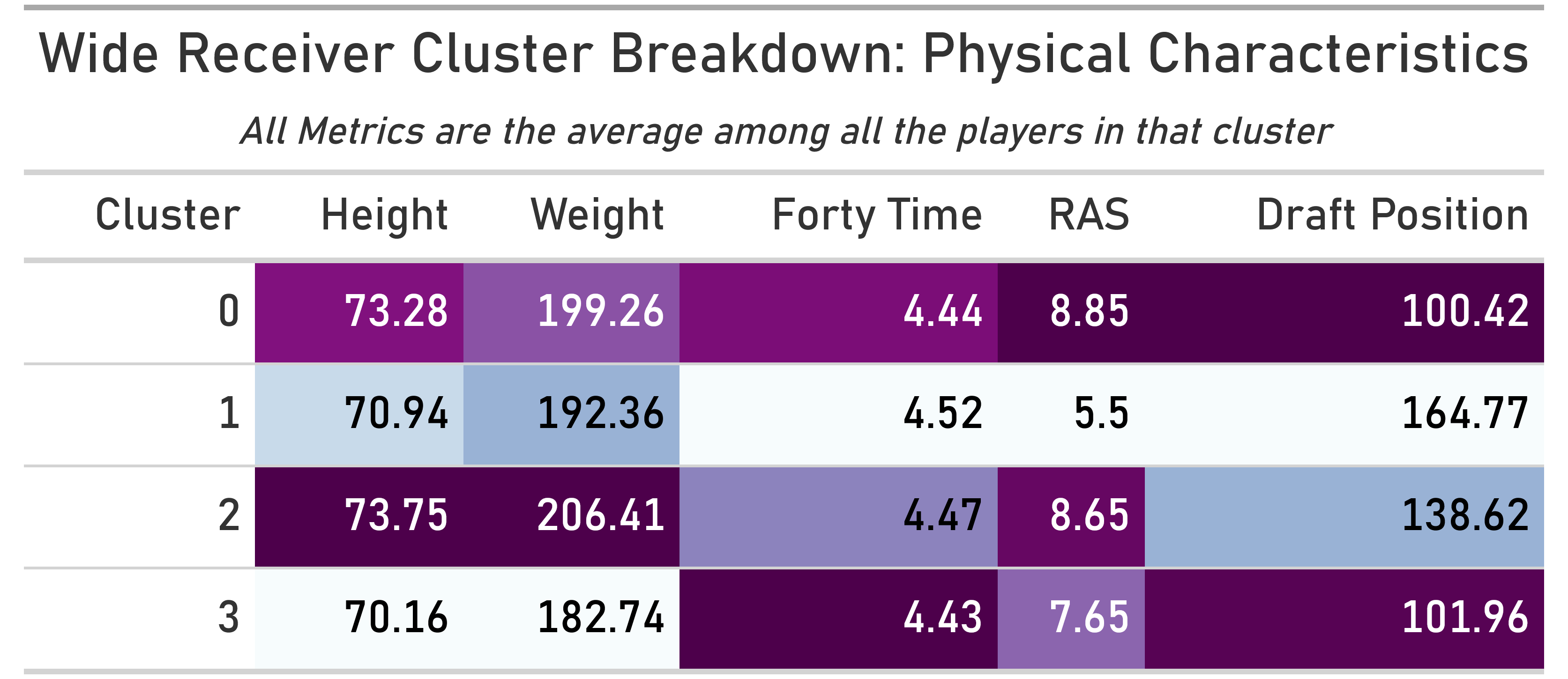

To begin answering our question about the various archetypes that currently exist in the NFL, it helps to get a physical profile of each of them and how those profiles are currently valued by NFL personnel. I used the nfl_data that we imported earlier and the feature data we have been working with to find the means of each cluster’s height, weight, forty time (speed), and draft position.

This table was really helpful for me to begin breaking down our clusters and figuring out how K-Means organized them. On my understanding, they are roughly as follows:

Cluster One: WR-1 Upside

This cluster featured the likes of Ja’Marr Chase, Malik Nabers, Brian Thomas Jr., Quentin Johnston, Treylon Burks, Xavier Legette, and Rome Odunze—all prospects highly touted coming out of college and were thought of being the “alphas” within their respective offenses. Not all of those guys reached those potential, but the combination of their physical attributes, elite college production, and overall lofty expectations + high upside make sense about why they were clustered together.

Some players, such as Ja’lynn Polk and Troy Franklin weirdly got grouped togetehr in this cluster, which I think is a bit odd given that those profiles likely fit much better in the “grit” category and “speedster” categories respectatively, but nevertheless, the prestige of this cluster is apparent.

Cluster Two: First Guy in, Last Guy Out

This cluster is really interesting, and is a conglomeration of some really incredible names. Spearheaded by Amon-Ra St. Brown and Puka Nacua, it also includes Derius Davis, Jayden Reed, Amari Rodgers, and Kayshon Boutte. All of these receivers might seem terriblely “average” on paper, and that is perhaps reflected in their lowest average RAS and draft position. However, as Nacua and St. Brown have showed, it’s the fundamentals in route running and work ethic that are really difficulty to quanitfy that have led to those two being such dominant forces in the NFL. These guys have a chip on their shoulder coming into the league, and it’s great to see them represented in our data.

Cluster Three: Physical Specimens

These players really were given incredible gifts: Tall, strong, and fast, they have all the tools to really perform well at the next level. We are talking about players like George Pickens, Keon Coleman, Jonathan Mingo, Cedric Tillman, and DeVaughn Vele—players that on paper check all the boxes but are perhaps less refined in other parts of their game like route running and catching. These players often had solid college careers, though not always spectacular, and are in need of heavy refinement to fully unlock their potential.

There are some odd players clustered here, like Smith-Njigba and Rashod Bateman, but I am guessing those guys are kind of in a tier betwen this cluster and the cluster above: not physically dominate but not inept either, and can likely fall in any of the clusters given the particular features.

Cluster Four: Speedsters

These receivers are known primarily for one thing: their ability to vertically stretch the field. Xavier Worthy, Chirs Olave, Zay Flowers, Garrett Wilson, and Calvin Austin III. These guys typically are on the lighter-side and are right behind the WR-1 upside in average draft position given how important speed has become in the modern game.

There are few weird outliers here as well, with Tank Dell (as mentioned earlier) and Jordan Addison particularly, but these two are likely here because the weight of them really factored into their eventual clustering decision.

With that knowledge, that helps answer our question about the major wide receiver archetypes and can really inform how our algorithim classified the receivers in the upcoming draft class:

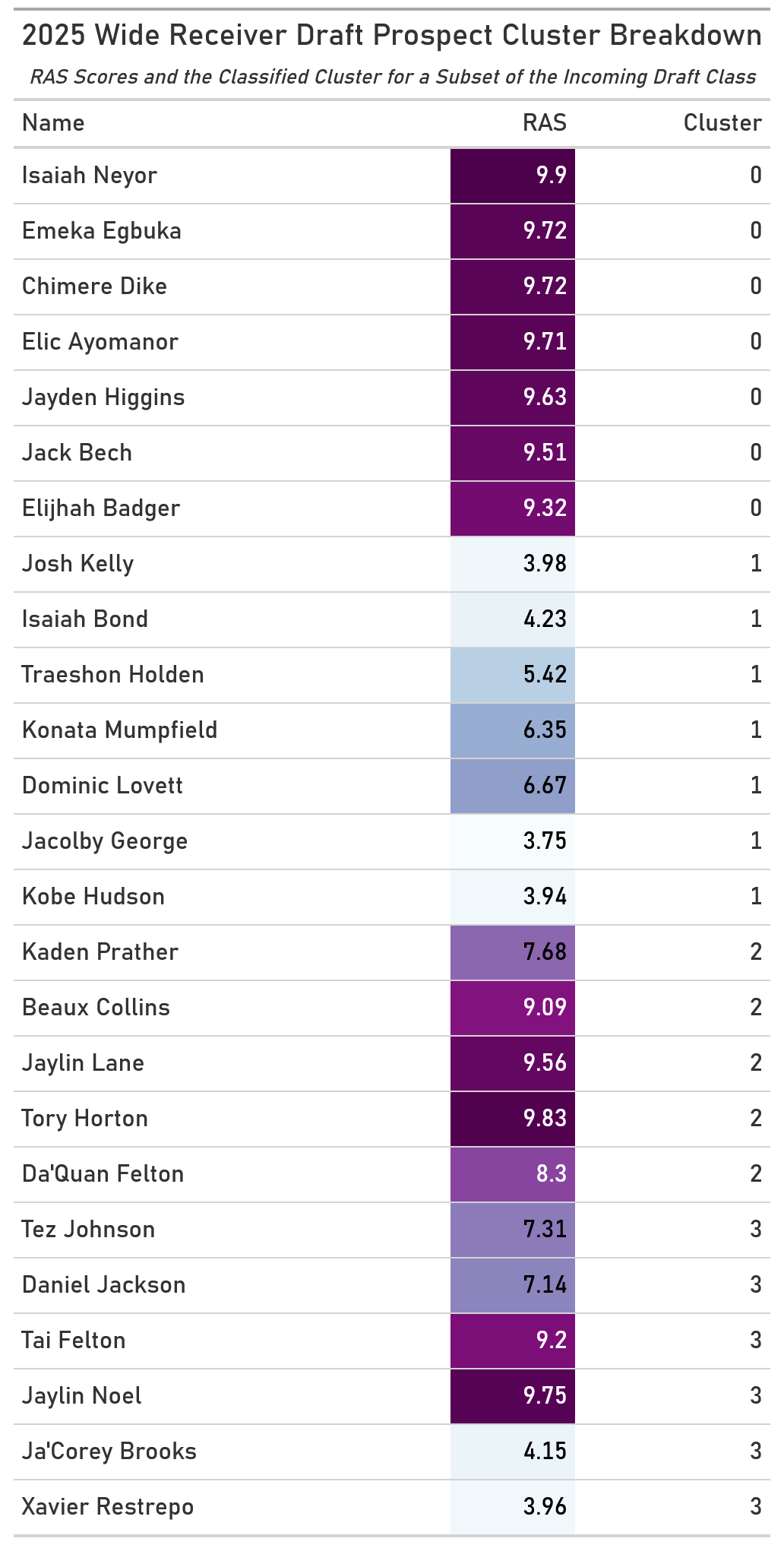

We can see some of the best receivers in the class, Emeka Egbuka, Jack Bech, and Jayden Higgins in that first category, while some of the guys in the second cluster are perhaps just waiting to become the next Puka Nacua or Amon-Ra St. Brown. The freakish athletes return in cluster 3, which includes 6’5 Da’Quan Felton and a bunch of receivers who are at least 6’3. The final category features the blazing fast Jaylin Noel and Tai Felton, though Xavier Restrepo’s real forty time of 4.8 was not included in the data for some reason (luckily for him because that was terrible).

VI. Impact & Conclusion

While there are quite a few outliers and head-scratchers throughout this project, I think this project really illustrates how valuable a holistic view of players can be and how marrying past-production with a player’s physical features can be very powerful in finding players like them. This model tends to sometimes priortize the combine metrics over the seasonal stats, which can lead to players like Smith-Njigba not really having a clear-cut cluster for them, but with a bit more tweaking and fine-tuning, I bet that can be alleviated. Finally, with the Draft being as much of an art as it is a science, this at least allows us to standardize part of the winding process of NFL drafting.

VII. References

- 2 Beautiful Ways to Visualize PCA

- CFBD API Documentation

- I leveraged ChatGPT to essentially sanity-check my clusters and bounce ideas off about the overall characteristics for each one

- as always, scikit-learn documentation and associated packages is always super helpful