Project Three - Catching the Bag: Forecasting the NFL Wide Receiver Contracts Based Upon Historical Statistics

I. Introduction

Amidst the donut-loving, chilly streets of New England persists one of the region’s most beloved and historic pastimes: sports. Having been born and spent the first twelve years of my life living in Massachusetts, I was practically indoctrinated in a fierce and persistent love for Boston sports teams—the Bruins, Red Sox, and Celtics all remain casual fandoms in my current life, but my absolute adoration for the New England Patriots and football has only blossomed in my years since departing the Bay State (perhaps due to the lack of a similarly successful equivalent in the Carolinas…).

With this very crucial backstory out of the way (trust me), we can finally launch into the main theme of this project: predicting the contracts of NFL players. In case you’re unfamiliar, most sports operate on a contractual basis, where players are signed to a team for a specific number of years for up to a specified amount of money. In the NFL, when these players’ contracts expire and are not renewed by the original team (a rationale that ranges from the player simply not being good enough anymore to financial constraints of the team), the player enters a period known as free agency. Now, any team (with some occasional, nuanced exceptions that are beyond the scope of this project), are able to offer a contract to the player in hopes that they bring their talents to a new franchise. As you can imagine, free agency period—which typically coincides with the start of the NFL New Year in mid-March—is a deeply exciting and turbulent time as generations of lives change overnight through the formulation and signing of unfathomably lucrative contracts. For instance, in this most recent 2025 free agency period alone, just looking at players who are wide receivers, we can observe the following contracts:

- Ja’Marr Chase (Cincinnati Bengals): $161,000,000 over 4 years, $40,250,000 average per year

- D.K. Metcalf (Pittsburgh Steelers): $131,999,529 over 4 years, $32,999,882 average per year

- Tee Higgins (Cincinnati Bengals): $115,000,000 over 4 years, $28,750,000 average per year

- Chris Godwin (Tampa Bay Buccaneers): $66,000,000 over 3 years, $22,000,000 average per year

- Devante Adams (Los Angeles Rams): $44,000,000 over 2 years, $22,000,000 average per year

Literally while working on this project, my beloved New England Patriots made a long-overdue splash for wide receiver Stefon Diggs, signing him to a massive 3 year, $63,500,000 deal for an average of $21,166,667 per year. With this obscene amount of money being thrown around, I think it is normal for both invested fans and even casual observers to ask: How much money should these players be made? What about their production on the field translates to their pay off the field?. To do this, we must launch in the world of regression and delve into the various models and techniques out there to predict continuous values. For simplicity, my project focuses on a very specific position in the NFL, the aforementioned wide receivers. However, the techniques and strategies explained below are equally applicable to any other positions (with different features and inputs of course).

I.II: Where did this data even come from?

Now, despite how popular the NFL is and how big of a deal NFL free agency has become, there is actually no easily accessible API or package for NFL salary data. That means I had to utilize every site administrator’s worst nightmare: web scraping. Luckily, there is an awesome site called overthecap.com that provides an immense amount of financial data and information about NFL players, updated daily. There is a very specific page that focuses upon contract history and has data spanning all the way back to 1985 and robust tracking since the early 2010s. Hence, some basic using BeautifulSoup parsing, I was able to quickly scrape OverTheCap and organize my data into a DataFrame that contains information like:

- Player Name

- Contract Sign Date

- Contract Value, Average Per Year (APY), and Length

- Whether the contract is still active

This financial data is coupled with statistical data courtesy of the nfl_data_py package, which is the Python Wrapper of the amazing nflverse project that has made a huge amount of NFL player data and advanced statistics available for free. For our use case where we are focusing on receivers, this includes vital stats like:

- A Player’s Height, Weight, and Age

- A Player’s Receiving Yards, Touchdowns, Receptions and Targets Per Season

- A number of advanced stats like Receiving EPA, Weighted Opportunity Rating, and Dominator Rating

These metrics will prove incredibly helpful in aiding our prediction, though as we will soon see, sometimes the most simple of calculations is all we need to make largely accurate predictions.

If you’d prefer to download this notebook, just press here.

II. How Does Regression Work?

I use three main regression models throughout this notebook, but they all stem from the grandfather of all regression models: Linear Regression.

Statistically, calculating linear regression for a single variable (a univariate function) relies upon a relatively simple equation to find the slope of our line, $\beta$, and the intercept, $\alpha$.

\[\beta = \frac{\sum{(x_i - \bar{x})(y_i - \bar{y})}}{(x_i - \bar{x})^2}\] \[\alpha = \hat{y} - \beta\hat{x}\]This analytical method works great for single variable functions, but doesn’t address the fact that many real-world problems involves a single variable depending on a variety of predictor variables, along with this approach doesn’t quite scale super-well computationally with the massive amounts of data that the modern world interacts with. Hence, the need for the closed-form solution, also known as Ordinary Least Squares. This utilizes an equation with a data matrix that stores all of our features and inputs for us, and uses some nifty matrix operations and matrix calculus to calculate the optimal weights for us with the following equation:

\[\hat{w} = (\mathbf{X}^\top \mathbf{X})^{-1} \mathbf{X}^\top \mathbf{y}\]$X$ here is our data matrix, which is simply a matrix-representation of our data, for instance, if I had data that looked like this:

| Receiving Yards | Touchdowns | Age |

|---|---|---|

| 1300 | 7 | 22 |

| 386 | 2 | 29 |

In a data matrix, that would look like:

\[\begin{pmatrix}1 & 1300 & 7 & 22\\\ 1 & 386 & 2 & 29\end{pmatrix}\]You can see we add an additional column of 1’s to represent our intercept or bias (of course, this can be any constant value, but 1 is traditional to start out with).

This OLS solution is awesome, and is in fact the method that scikit-learn uses underneath the hood with the LinearRegression class [1] but faces one main drawback: calculating $(\mathbf{X}^\top \mathbf{X})^{-1}$ can be a very expensive operation with very large datasets. Hence, there is one last approach, Least Mean Squares or also known as Linear Regression with Gradient Descent that adopts a more iterative optimization approach to deal with larger datasets that may take too long to run with OLS or work with data matrices that might not even fit into the memory of our machine to do the inversion.

With this method, we are initializing our weights to random values and leveraging a hyperparameter called learning rate, $\alpha$ or $\eta$ (depending on where you look), to iteratively tweak our weights. The key behind any gradient descent process is a loss function, which in this case is $J(\mathbf{w}_{old})$. We can have a variety of loss functions, but the idea is that they represent the difference between the our true labels and the values we are currently predicting. We want to minimize this of course, hence why we take the gradient of it and subtract it from our current weights. In the case of Linear Regression, our loss function is really nice, the mean squared error:

\[J(\mathbf{w}_{old}) = \frac{1}{n}\sum{(x_{i}^\top \mathbf{w}_{old} - y_{i})^{2}} = \frac{1}{n}\sum{(\hat{y} - y_{i})^{2}}\]It looks really complex, but it is really just finding the difference our our predicted value and true value and averaging that difference over the entire dataset. I utilize a univariate Linear Regression Model below and it performs not great, but given how simple it is, much better than I anticipated!

The other models I use are summarized below, with a brief description for each:

- Decision Trees: While decision trees are awesome for classification, we can also utilize them for regression while working with numerical values. They also work to minimize a statistic like MSE and split based on that instead of Gini Index or entropy; the leaf nodes are predicting numerical values instead of the predicted class.

- Random Forests: Super similar idea to Decision Trees and their versatility, but they take it further by being an ensemble model that combines many weak decision trees together to usually create more powerful, robust predictions that are less prone to overfitting compared to a normal decision tree.

- XGBoost: XGBoost is yet another ensemble model that is very efficient and effective, and among one of the most popular models for both classification and regression. To be honest, I don’t quite fully understand the nuances of gradient boosting quite yet but I know that it involves the “multiple-models” approach of random forests with the minimizing loss function through gradients that we discussed earlier with least mean squares. There is a really easy to use Python package that is super compatible with scikit-learn, so I decided to give it a go!

III. Data Understanding and Pre-Processing

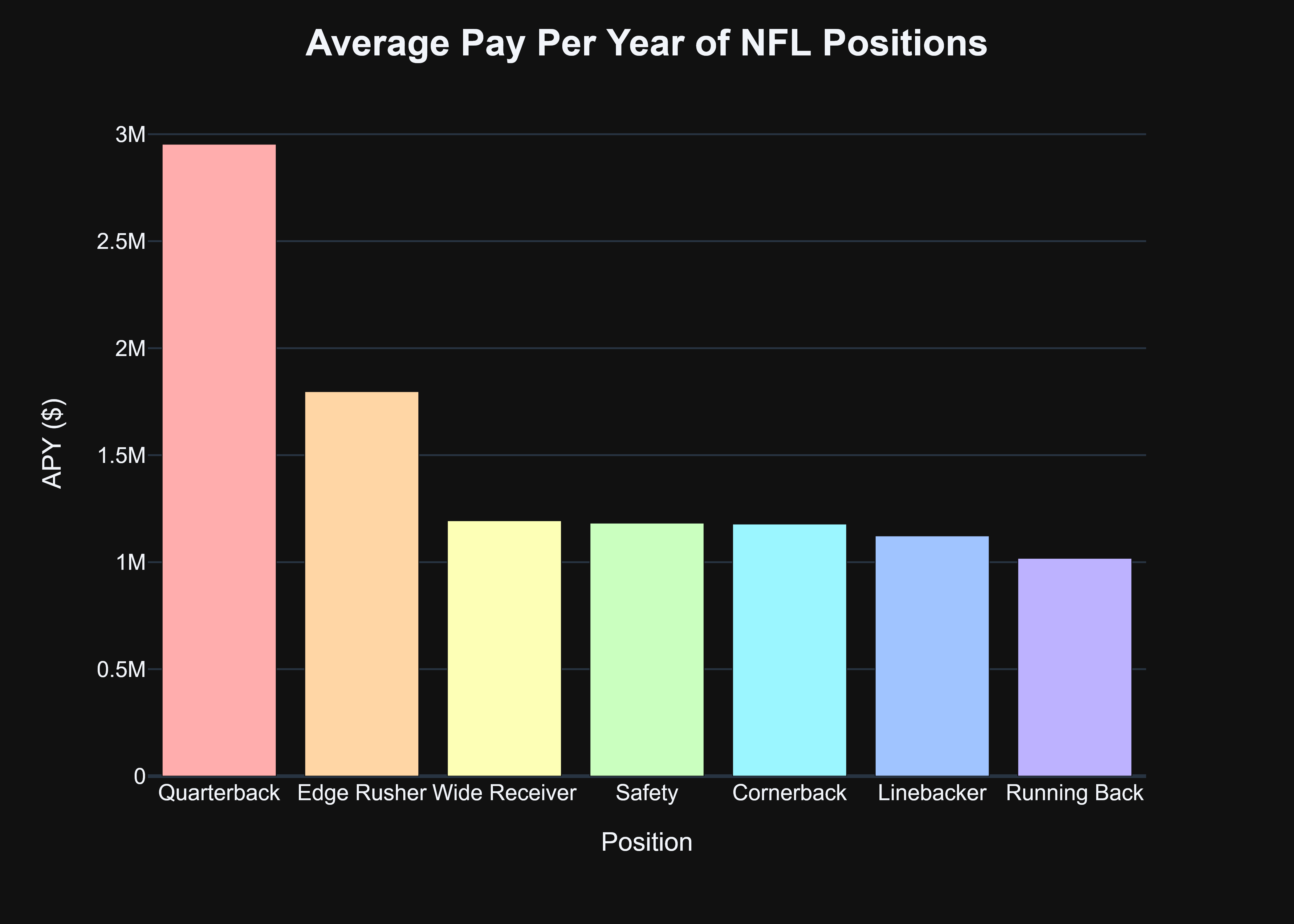

Given that I created the financial dataset myself, much of the pre-processing and formatting was already done when I collected the data. To get a better idea of why I decided to just focus on the wide receivers instead of creating a more general model to all predictions, we can quickly visualize the average salary values by position:

This chart can provide some really helpful insight into why a general model wouldn’t perform great: there is so much variation in the pay per position. Yes, we could obviously use pay as a feature and that would help, but in my mind, creating a tailored model on a per-position basis can allow so much more fine-tuning and adapting that you can only get on a granular scale. Receivers to me met the middle ground of being a valued position while not being so far down that their contracts are not particularly interesting (see other positions not even listed here like center, guard, or punter).

With that solidified, we can move onto cleaning and processing the analytical data. To do that, I first had to use the pandas .join() methods to combine multiple stats datasets together and then had to do some name alterations to ensure that the names in this dataframe were consistent with the ones in the salary one:

# Create a dictionary to hold the player name corrections

name_corrections: dict = {

"DK Metcalf": "D.K. Metcalf",

"Devonta Smith": "DeVonta Smith",

"Michael Pittman": "Michael Pittman, Jr."

}

# Apply the corrections to the nfl_data DataFrame

for old_name, new_name in name_corrections.items():

nfl_data.loc[nfl_data['player_name'] == old_name, 'player_name'] = new_name

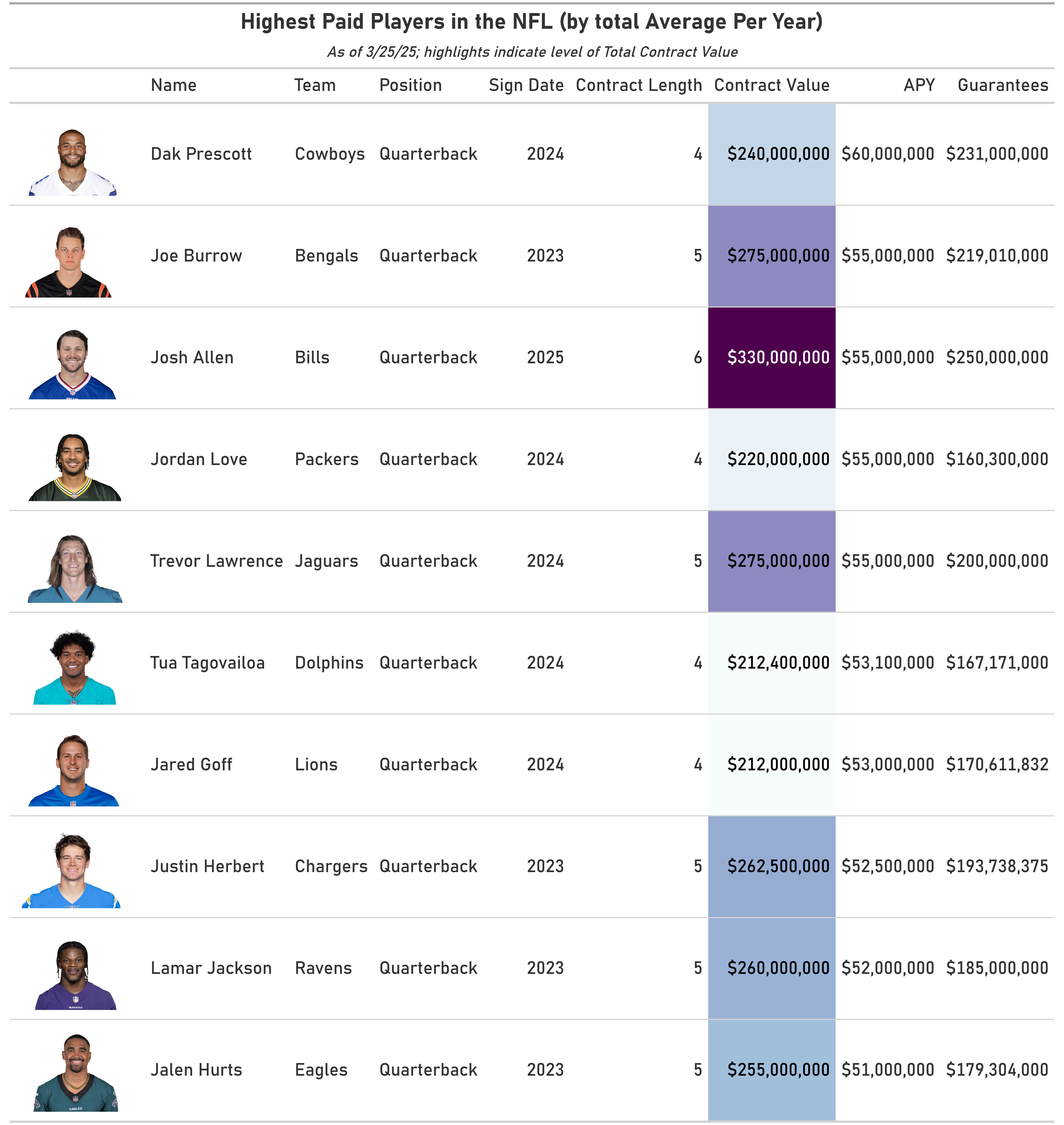

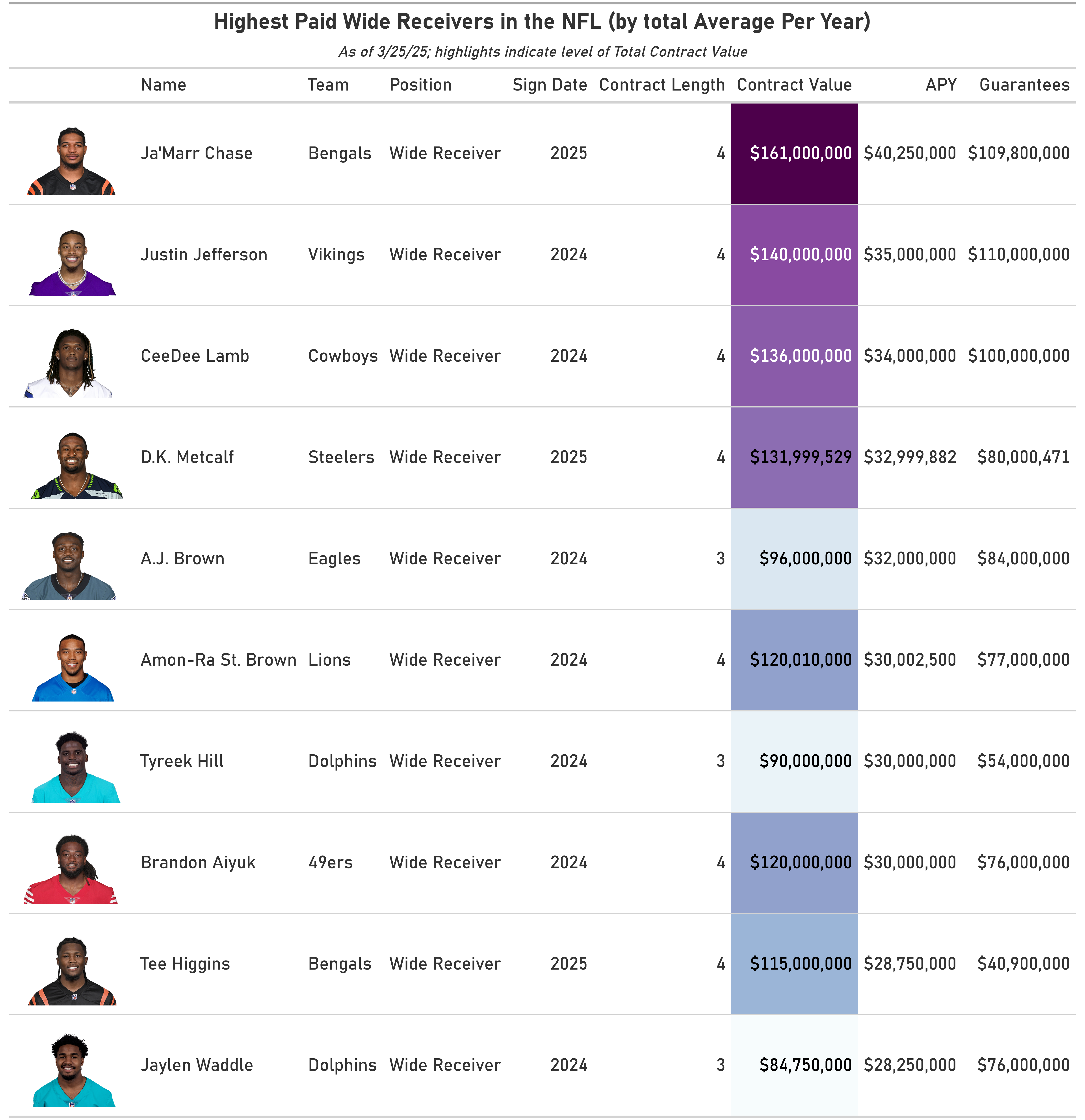

With that out of the way, I decided to take a look at the top salaries overall in the NFL and because I had access to headshots via nfl_data_py, I decided to have some fun and make some nice tables:

This illustrates yet another reason why I think going with wide receivers is much better than focusing on the most flashy position, quarterback. If you look at the highest paid players list (which is exclusively QBs), some of the players there are really good and are among the best in their position. But some of the players there kinda suck and don’t really have the statistical feats of their peers to make an algorithmic approach predicated historical stats really feasible (tldr; Trevor Lawrence and Tua Tagovailoa are over-paid and would likely mess up my model). On the other hand, all of the wide receivers paid within the top ten are essentially the best-of-the-best only and all of them have strong cases to be in that list (some cases are stronger than others though).

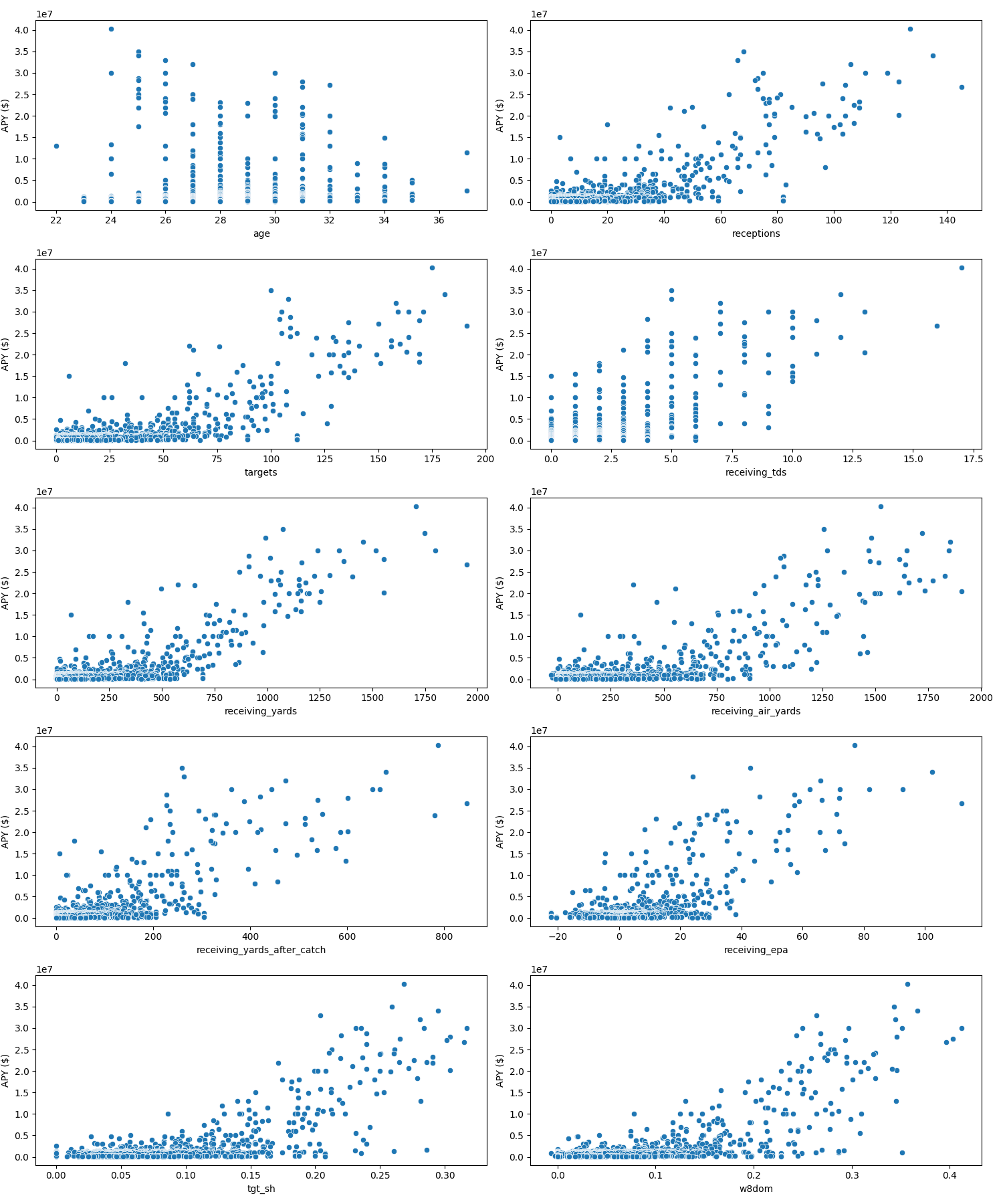

The nfl_data_py dataframe gives a great deal of information, and most of it isn’t particularly relevant, so I parsed it down to nine relevant features that I believe are most critical to this prediction (all of these are per season): player’s age, receptions, targets, receiving touchdowns, receiving yards, receiving air yards, receiving yards culminated after a catch, receiving EPA, target share, and weighted dominator score. To tackle our first experiment with using a simple linear regression model, I plotted each against the our target, which I decided to be average pay per year instead of contract value due to it being a bit more normalized against long, potentially misleading contracts.

IV. Experiment One: Univariate Linear Regression

Having already gone in-depth about Linear Regression and now identified the trends of our relevant features, we can finally begin some actual modeling. There is a slight problem, none of our features really look strictly linear, and in fact, most of them have a pretty similar trend line if we plotted a single one for each feature individually. To make it simple, I picked the most most straightforward feature, receiving yards, for my univariate linear regression model. As with any model, we first begin by splitting our data into relevant datasets:

basic_X_trn: np.ndarray

basic_X_tst: np.ndarray

basic_y_trn: np.ndarray

basic_y_tst: np.ndarray

# We have to use reshape here to turn our row vectors into column vectors

basic_X_trn, basic_X_tst, basic_y_trn, basic_y_tst = train_test_split(combined_stats['receiving_yards'].values.reshape(-1, 1), combined_stats['APY ($)'].values.reshape(-1, 1), test_size = .33, random_state = 42)

As with any scikit-learn model, creating and fitting our model is literally just two lines, which is awesome:

basic_model: LinearRegression = LinearRegression()

basic_model.fit(basic_X_trn, basic_y_trn)

Given that we are doing quite a bit of repeated evaluation throughout this project that is essentially the same sequence over and over again, I decided to create a helper function evaluate_model that helps speed up this process a bit. It simply takes in the model to evaluate, the relevant training & test datasets, and then also a list of metrics that we want to evaluate the model on, calculating each metrics on both the training & test datasets:

from sklearn.base import BaseEstimator

from typing import Callable

def evaluate_model(model: BaseEstimator, X_trn: np.ndarray, X_tst: np.ndarray, y_trn: np.ndarray, y_tst: np.ndarray, metrics: list[Callable[[np.ndarray, np.ndarray], float]], model_name: str = 'model', verbose: bool = True) -> tuple[dict[str, float], np.ndarray, np.ndarray]:

"""Calculate the metric scores for a model

Args:

model (BaseEstimator): scikit learn model to use for evaluation

X_trn (np.ndarray): training input for the model

X_tst (np.ndarray): testing input

y_trn (np.ndarray): training output

y_tst (np.ndarray): testing output

metrics (list[Callable[[np.ndarray, np.ndarray], float]]): metrics to evaluate the model on; from sklearn.metrics

model_name (str, optional): name of the model to use in print statements. Defaults to 'model'.

Returns:

tuple[dict[str, float], np.ndarray, np.ndarray]: metrics of the model, train predictions of model, and test predictions

"""

metric_scores: dict[str, float] = {}

# Calculate the training metrics

train_preds: np.ndarray = model.predict(X_trn)

for metric in metrics:

metric_name: str = metric.__name__.replace('_', ' ').title()

metric_score: float = metric(y_true = y_trn, y_pred = train_preds)

metric_scores[f'{metric_name}_train'] = metric_score

if verbose:

print(f'The {metric_name} on the training data of our {model_name} is {metric_score:,.4f}')

# Calculate the test metrics

test_preds: np.ndarray = model.predict(X_tst)

for metric in metrics:

metric_name: str = metric.__name__.replace('_', ' ').title()

metric_score: float = metric(y_true = y_tst, y_pred = test_preds)

metric_scores[f'{metric_name}_test'] = metric_score

if verbose:

print(f'The {metric_name} on the testing data of our {model_name} is {metric_score:,.4f}')

return metric_scores, train_preds, test_preds

We can then use this function to do much of the evaluation for us:

basic_eval, basic_train_preds, basic_test_preds = evaluate_model(model = basic_model, X_trn = basic_X_trn, X_tst = basic_X_tst, y_trn = basic_y_trn, y_tst = basic_y_tst, metrics = [root_mean_squared_error, r2_score], model_name = 'Basic Linear Regression Model')

# Output

The Root Mean Squared Error on the training data of our Basic Linear Regression Model is 2,983,494.0606

The R2 Score on the training data of our Basic Linear Regression Model is 0.6813

The Root Mean Squared Error on the testing data of our Basic Linear Regression Model is 2,798,006.3796

The R2 Score on the testing data of our Basic Linear Regression Model is 0.4157

That’s not particularly great, let’s quickly visualize our line to see how close it is to the actual points (I created another helper function called make_plot but forgot that my future models will use more than one feature, making it pretty difficult to plot.)

basic_plot = make_plot(basic_X_tst, basic_y_tst, basic_test_preds, "Basic Linear Regression: Just Using Receiving Yards")

plt.show()

So based on this woeful model performance and the previous scatterplot we made, we can clearly see that relying upon a model that uses just a single feature is not going to be nearly enough to succeed. Thus, let’s move on to the next part: multivariate regression.

V. Experiment Two: Multivariate Regression Models

Before we delve into using more sophisticated models, it’s clear that we are going to need to buff up our training and test data to include the relevant features that we identified earlier.

Wide Receivers have a big of flexibility in the NFL, and some players who are actually listed as a Wide Receiver never play the position at all but instead serve as integral pieces of a team’s special teams (see Patriots legend Matthew Slater). Players that fill into this bucket typically have their weighted dominator score be 0, so we will do a little bit of data pre-processing here and simply drop those rows (it’s only a small handful of players affected).

# Let's create a new training set that relies on a few more features

X_trn: np.ndarray

X_tst: np.ndarray

y_trn: np.ndarray

y_tst: np.ndarray

# Some receivers just play special teams and don't necessarily really play as a traditional Wide Receiver, so if there w8dom value is NaN here, we can assume they fall into that category

X_trn, X_tst, y_trn, y_tst = train_test_split(combined_stats[rel_features].dropna(axis = 0, how = 'any', subset = 'w8dom').values, combined_stats.dropna(axis = 0, how = 'any', subset = 'w8dom')['APY ($)'].values.reshape(-1, 1), test_size = .33, random_state = 42)

With these dataset, we can follow a very simple sequence of method and steps to our linear regression model for our next model: A Decision Tree.

# Testing out a Decision Tree

tree_model: DecisionTreeRegressor = DecisionTreeRegressor()

tree_model.fit(X_trn, y_trn)

tree_eval: dict

tree_train_preds: np.ndarray

tree_test_preds: np.ndarray

tree_eval, tree_train_preds, tree_test_preds = evaluate_model(model = tree_model, X_trn = X_trn, X_tst = X_tst, y_trn = y_trn, y_tst = y_tst, metrics = [root_mean_squared_error, r2_score], model_name = 'Decision Tree Regression Model')

The Root Mean Squared Error on the training data of our Decision Tree Regression Model is 291,430.6363

The R2 Score on the training data of our Decision Tree Regression Model is 0.9970

The Root Mean Squared Error on the testing data of our Decision Tree Regression Model is 2,288,790.0169

The R2 Score on the testing data of our Decision Tree Regression Model is 0.6443

We are already seeing much better performance! But, look at the discrepancy in the training metrics and the testing metrics; that is a massive difference and a clear sign of overfitting. Seeing this, I realized that I needed to figure out why this was happening and potential steps to mitigate it. First off, was there a particular feature that the Decision Tree was overfitting to especially?

# What feature is our model overfitting to?

pd.Series(tree_model.feature_importances_, combined_stats[rel_features].columns).sort_values(ascending = False)

receiving_yards 0.806376

tgt_sh 0.060913

targets 0.038668

w8dom 0.029500

receiving_epa 0.017403

receiving_air_yards 0.016052

age 0.013541

receptions 0.007803

receiving_yards_after_catch 0.005176

receiving_tds 0.004569

dtype: float64

Ah! So we see a huge part of our model’s predictions is just looking at the player’s receiving yards (which we saw above isn’t necessarily the best idea) and then using the other features as essentially afterthoughts to tune its predictions. Now, we have to ask ourselves is this a problem?. The model overfitting certainly is, but is just dropping receiving yards the real solution? Because, NFL teams certainly do look at receiving yards as a major indicator of how to structure a player’s contracts, and in many regards, receiving yards is the most important statistic for a WR. I did some experimentation, specifically some ablation tests where I dropped receiving yards and evaluate the performance.

# Let's see if we can remove receiving_yards to get similar accuracy

rel_features.remove('receiving_yards')

X_trn, X_tst, y_trn, y_tst = train_test_split(combined_stats[rel_features].dropna(axis = 0, how = 'any', subset = 'w8dom').values, combined_stats.dropna(axis = 0, how = 'any', subset = 'w8dom')['APY ($)'].values.reshape(-1, 1), test_size = .33, random_state = 42)

tree_model.fit(X_trn, y_trn)

tree_eval, tree_train_preds, tree_test_preds = evaluate_model(model = tree_model, X_trn = X_trn, X_tst = X_tst, y_trn = y_trn, y_tst = y_tst, metrics = [root_mean_squared_error, r2_score], model_name = 'Decision Tree Regression Model')

The Root Mean Squared Error on the training data of our Decision Tree Regression Model is 291,430.6363

The R2 Score on the training data of our Decision Tree Regression Model is 0.9970

The Root Mean Squared Error on the testing data of our Decision Tree Regression Model is 2,176,075.7494

The R2 Score on the testing data of our Decision Tree Regression Model is 0.6785

# View new feature importances

pd.Series(tree_model.feature_importances_, combined_stats[rel_features].columns).sort_values(ascending = False)

tgt_sh 0.696595

targets 0.114698

w8dom 0.055644

receiving_air_yards 0.052225

receiving_epa 0.035021

age 0.016034

receiving_yards_after_catch 0.012006

receiving_tds 0.009475

receptions 0.008303

dtype: float64

We find ourselves getting nearly identical performance with the model having a more balanced feature importance index. Hence, I decided to remove receiving_yards as a way to hopefully make our model more generalizable, interpretable, and less prone to overfitting. I utilize this new updated feature list for my next model, which also aims to combat overfitting by combine multiple decision trees together: random forests.

# Let's try to over-combat the overfitting with an ensemble model

rf: RandomForestRegressor = RandomForestRegressor()

rf.fit(X_trn, y_trn.ravel())

rf_eval: dict

rf_train_preds: np.ndarray

rf_test_preds: np.ndarray

rf_eval, rf_train_preds, rf_test_preds = evaluate_model(model = rf, X_trn = X_trn, X_tst = X_tst, y_trn = y_trn, y_tst = y_tst, metrics = [root_mean_squared_error, r2_score], model_name = 'Random Forest Regression Model')

The Root Mean Squared Error on the training data of our Random Forest Regression Model is 797,022.3446

The R2 Score on the training data of our Random Forest Regression Model is 0.9779

The Root Mean Squared Error on the testing data of our Random Forest Regression Model is 1,852,110.1425

The R2 Score on the testing data of our Random Forest Regression Model is 0.7671

We can see that we get an instant boost in out testing accuracy at minimal decrease in our trainining accuracy, and if we inspect the feature importances for the random forest model, we get a much more balanced picture:

tgt_sh 0.385418

receiving_air_yards 0.301290

w8dom 0.064857

targets 0.062970

receiving_yards_after_catch 0.055652

receiving_epa 0.051901

receptions 0.051064

age 0.015059

receiving_tds 0.011789

dtype: float64

We are striking a good medium of using target share and receiving air yards to predict now, however the weighted dominator factor, target, and receptions all have notable impacts on the final predicted score.

Finally, we can move onto our last model: XGBoost. Even though this not directly from the scikit-learn library, it’s objects and methods are directly compatiable with the library and the code is essentially identical

# Another ensemble method, but maybe even more generalizable and powerful: XGBoost!

xgboost: XGBRegressor = XGBRegressor()

xgboost.fit(X_trn, y_trn)

xgboost_eval: dict

xgboost_train_preds: np.ndarray

xgboost_test_preds: np.ndarray

xgboost_eval, xgboost_train_preds, xgboost_test_preds = evaluate_model(model = xgboost, X_trn = X_trn, X_tst = X_tst, y_trn = y_trn, y_tst = y_tst, metrics = [root_mean_squared_error, r2_score], model_name = 'XGBoost Regression Model')

The Root Mean Squared Error on the training data of our XGBoost Regression Model is 293,540.1383

The R2 Score on the training data of our XGBoost Regression Model is 0.9970

The Root Mean Squared Error on the testing data of our XGBoost Regression Model is 1,902,217.4789

The R2 Score on the testing data of our XGBoost Regression Model is 0.7543

We can see that the latter two models do very similarly in performance, and all of them can be helpful in trying to acocomplish our ultimate goal: predicting these contracts. With these enhanced models out of the way, we can move onto the culminating experiement: hyperparameter tuning.

VI. Experiment Three: Hyperparameter Tuning

I utilized hyperparameter tuning last project, and none of my models gave me even useable results until I did. My accuracy for this project is a bit better this time around, so I am not expecting so drastic of an improvement, but at least noticable growth is RMSE and $R^2$ would be great.

The process for all three models—decision trees, random forests, and XGBoost—is essentially identical, with the only difference being the actual parameters we are tuning of course. For reference, I show the code for the XGBoost tuning below:

xgboost_param_grid: dict[str, list[Union[str, int]]] = {

"learning_rate" : [0.05,0.10,0.15,0.20,0.25,0.30],

"max_depth" : [ 3, 4, 5, 6, 8, 10, 12, 15],

"min_child_weight" : [1, 3, 5, 7 ],

"gamma": [0.0,0.1,0.2 ,0.3,0.4 ],

"colsample_bytree" : [0.3,0.4,0.5 ,0.7 ]

}

xgboost_random_search: RandomizedSearchCV = RandomizedSearchCV(

estimator = XGBRegressor(random_state=42),

param_distributions = xgboost_param_grid,

cv = 5,

scoring = ["neg_root_mean_squared_error", "r2"],

refit = "neg_root_mean_squared_error",

verbose = 1,

n_iter = 11

)

xgboost_random_search.fit(X_trn, y_trn.ravel())

tuned_xgboost: XGBRegressor = xgboost_random_search.best_estimator_

print(f'The best estimator parameters were: {xgboost_random_search.best_params_}')

tuned_forest_eval, tuned_forest_train_preds, tuned_forest_test_preds = evaluate_model(model = tuned_xgboost, X_trn = X_trn, X_tst = X_tst, y_trn = y_trn, y_tst = y_tst, metrics = [root_mean_squared_error, r2_score], model_name = 'Tuned XGBoost Regression Model')

The results for all of the models, including the hyparameter tuned ones, can be found below:

This table shows us that while hyperparameter tuning definietely helped our models here, it wasn’t the parameters themselves this time that needed to be radically changed to improve performance. Instead, our models might benefit from other measures like regularization to further improve performance and generalizability. Oh well, that’s for another project.

VII. Conclusion and Impact

One of the biggest impacts of a project like this is that currently contract negotations demand an intimate knowledge of the current market for a player and how a player’s stats translate into tangible financial value. This can help provide players that are representing themselves or athletes that are a bit earlier into their career that cannot quite afford an expensive agent to get a rough estimate about how their production thus far translates to NFL dollar amounts. However, one of the drawbacks is that there are so many aspects that go into contract agreements that is deeply unquantifable, at least not readily; how much a player likes or dislikes a particular geogrpahic location, the increased tax rates in one state compared to another that can inflate the final APY, or the famous “hometown discount” that players like Tom Brady took for years so that the team could sign players that put them in a better position to win. These things are beyond the scope of nearly any machine learning model, and certainly mine.

However, what we did see is that what matters in terms of differentiating the pay day for various NFL wide receivers is relatively simple, the stats that have been tracked since the conception of the game of football: receiving yards and how prominent a player is within their offense (the latter has not been numerically calculated for as long as the former, but both have historically been very easy to spot). Additionally, I learned that creating datasets is a lot more time intensive and laborious than it seems and I am inifintely grateful for the incredible work by millions of people on Kaggle, scientific labortories, and countless other entities that take the time to collect, normalize, and parse much of this data for us. Finally, while my previous project showed the immense power of hyperparameter tuning, this one showed that it certainly can’t be the only avenue to improve performance and should, as with many things in machine learning, be one of the many tools that we utilize in order to make our models more robust and usable in the everday world.

VIII. References

Beautiful Soup Documentation

XGBoost for Regression

Hyperparameter Tuning for XGBoost

Special shotout to the scikit-learn, great_tables, and seaborn documentation :)